Autobiographical Fiction reflecting on Troubled Times

In troubled times of our own, with the rise of ‘populist politics’ it seems both sad and sagacious to be drawn back into a re-read, a fictionalised account by Christopher Isherwood, of time spent in the Weimar Republic, primarily in Berlin, between 1930 and 1933.

In troubled times of our own, with the rise of ‘populist politics’ it seems both sad and sagacious to be drawn back into a re-read, a fictionalised account by Christopher Isherwood, of time spent in the Weimar Republic, primarily in Berlin, between 1930 and 1933.

Goodbye to Berlin, first published in 1939, is a collection of six short stories or novellas, with a cast of characters who sometimes reappear in more than one story, all linked together by the narrator ‘Christopher Isherwood’

In a short foreword, Isherwood reminds the reader that although he has given his name to the ‘I’ narrator, we should not assume that this is purely autobiography, or that the characters with the pages are EXACT portrayals of the other people. Isherwood points out that “Christopher Isherwood” should be regarded as a kind of “convenient ventriloquist’s dummy”

However, those interested in the man and his writings certainly can read biographies which let the reader know which real individuals are being described.

Goodbye to Berlin of course also later appeared as a stage play ‘I Am A Camera’ – a direct quote from the book itself, as, very early on Isherwood states what he intends this writing to be

I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking. Recording the man shaving at the window opposite and the woman in the kimono washing her hair. Some day, all this will have to be developed, carefully printed, fixed

And, of course, one of the central novellas in this collection is “Sally Bowles” and that particular story gave rise to the successful musical and even more successful film, Cabaret.

To return to the book, it is Isherwood’s creation of his “Christopher Isherwood” ventriloquist’s dummy – or camera – which gives the book its cool power. He casts himself, and is, the Englishman abroad, drawn to the unprovincial, dangerous, decadent, colourful and extreme life of Berlin, where personal and political morality is open, not hidden, where political extremes walk the streets, and where, quite quickly everything is in change and confusion. Isherwood makes his ‘dummy’ an interested-in-everything observer. It is the very reverse of polemic writing – though it is always clear where the writer’s mind, heart and moral judgement lies.

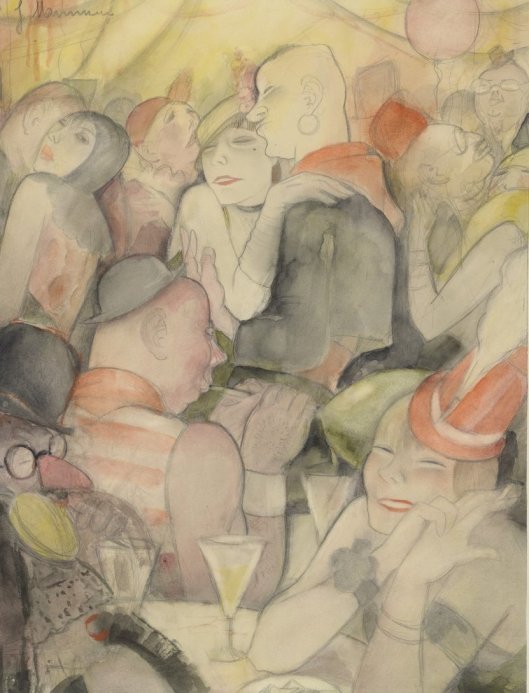

Jeanne Mammen – Carnival in Berlin

Starting in 1930, the narrator, earning his (small) living by teaching English, is staying in a not quite respectable boarding house, run by an impoverished ageing woman, who rather turns a blind eye to the fact that one of her guests earns her living on her back, whilst another, a not particularly talented cabaret artiste, is an ardent Nazi (at that time, just a rather laughable party led by a silly little man no one really expected to go anywhere). The book ends in 1933, when the silly little man has formed a cabinet, and ardency in populist politics is clearly going in the direction it does, or, as Isherwood observes, about his landlady:

Already she is adapting herself, as she will always adapt herself to every new regime. This morning I even heard her talking reverently about “Der Führer” to the porter’s wife. If anybody were to remind her that, at the election last November, she voted communist, she would probably deny it hotly, and in perfect good faith. She is merely acclimatizing herself, in accordance with a natural law, like an animal which changes its coat for the winter. Thousands of people like Frl. Schroeder are acclimatizing themselves. After all, whatever government is in power, they are doomed to live in this town

And in between Isherwood’s arrival in 1930 and departure in 1933, the writer introduces us to a brilliant mix of messy humanity. There are three major stories to follow – Sally Bowles, the louche daughter of a wealthy English family come to Berlin to be an artiste and to enjoy sexual freedom; The Nowak Family, almost on their uppers, whom Isherwood lodges with when he is so poor that he can’t even afford to stay at Schroeder’s any more, and the wealthy, liberal established German Jewish family The Landauers.

The writing, like the humanity, is wonderful

‘Goodbye to Berlin’ as a title, also demonstrates the layers of meaning Isherwood packs into his clear and deceptively simple prose. This is not just Isherwood saying ‘Goodbye to Berlin’ at the end of his stay – it is Berlin, saying goodbye to itself.

Great review. It would definitely be nice to follow a narrator who teaches English and stays in a borading home. I feel the connection already

It’s a great book!

I read this a couple of years ago and enjoyed it. To date it’s the only Isherwood I have read. I loved the atmosphere of the boarding house and the characters who live there.

Mr Norris Changes Trains and this one were my only Isherwoods, both read decades ago. And I think it was either you, JacquiWine, Kaggsy or Shoshi, reviewing Norris that made me raid my shelves for the falling apart version of this one, and tracking down a second hand Norris . I want to read more now.

I’m afraid it wasn’t me, though I do love both books. Thank you for this reminder of ‘Goodbye to Berlin’; it really is a wonderful, if frighteningly pertinent, novel.

I regard the four of you as my Four Bookie Musketeers!

Excellent review Lady F. That quote you pick out about people adapting themselves to the prevailing political climate is quite chilling…

Indeed. It’s a distressing read. When I read it first, some time in the early 80s, I think, it was with the sense that all that was hopefully behind, its lessons and warnings learned. But now, though I read it with great fondness and appreciation of Isherwood’s craft, I was also reading with a sense of mounting unease, and that quote slapped me about a bit. Chilling, as you say

So many uncomfortable echoes – quite chilling! We can but hope that we manage to detour away from following the same path – on both side of the Atlantic…

I know. Who would have thought these books might have had urgent things to say to our times.

Oh it’s been a long time since I read this one, I’d love to go back to it now I’m older and possibly wiser!

I’m really appreciating re-reading these writers from the first half of the twentieth. Disciplined and precise, wearing their education lightly, knowing how to keep their prose deceptively simple.

Wonderful review Lady F, I love your closing comment. Having read A Single Man quite recently, I’m keen to read more Isherwood. This sounds compelling.

Thank you Madame Bibi – clearly, I should investigate A Single Man

It is the very reverse of polemic writing – though it is always clear where the writer’s mind, heart and moral judgement lies.

And this is what makes it such a wonderful piece of fiction and testimony of the times. It captures the confused atmosphere so well. Thank you for a great review. And no, I’m not frightened at all that we are heading the same way nowadays *runs shrieking down the corridor!*

I come back, again and again, to W.B. Yeats’ wonderful, and sobering, poem ‘The Second Coming’ with the lines

‘The best lack all conviction, whilst the worst

Are full of passionate intensity’

circling almost endlessly in my head, whilst pictures of leading political hopefuls are shown on TV news, and stories of yet more outrages are told. In some ways, the political hopefuls driven by megalomania and fuelled by an internal anger and hate are the worst, as they provide the inflammatory tinder for others, those small, ordinary, unknown individuals. It makes no matter what the ‘great’ and the far from good are spouting, or where their anger and hatred are focused, it is energy of ‘the blood-dimmed tide’ they are loosing, steadily drowning ‘The ceremony of innocence’ and helping to birth Yeats’ ‘rough beast, its hour come at last’

So, yes I’m shrieking as I run down the corridor too! Either that, or finding at least some small, temporary escape from the gathering madness by wandering in meadows, looking at flowers and listening to birds. They give some honeyed sweetness to escape to, in my mind, when the news threatens to drown, overwhelm and suffocate us with despair

I just read something to that effect – about finding refuge in nature. The amount of nature writing published currently in the UK is on the up and up, incidentally.

https://www.the-pool.com/life/life-honestly/2016/30/sali-hughes-on-nature-and-nature-programmes

And yes, I agree with you: it’s the legitimization of ugly voices, providing the tinder for the more dangerous which I despise and fear most of all.

Thank you for that link, MarinaSofia. Though I’ve always lived in cities, I’ve also always known that the natural world is my link to sanity. In pain, in sadness, in rage, in despair, plus of course in joy and in faith and in delight and in serenity, listening to its serenity – and its indifference to my individuality, whilst it accepts the livingness of me – not to mention, how the dyingness of creatures will form part of its wider livingness – is solace, strength and a source of a deep joy.

I’m currently deep within a wonderful book about walking which won’t make it onto here until next year (when its publication date happens) which is really helping to ground me. It is beautifully written. If it comes your way, on Vine or The Galley, well worth grabbing! Christopher Somerville, The January Man